By Chryshane Mendis

Research into the field of Archaeology in Sri Lanka dates back to over 125 years, having being initiated by the British administration in the late 19th century. Archaeology as a professional discipline began in the early 19th century in Europe and as a result of our colonization by the British, the discipline found its way to the island from early on. Since then the archaeological field in Sri Lanka has been dominated first by the foreigners and after independence by the Sri Lankans, and has greatly aided in our understanding of our rich history. A large percentage of what we know of and all of what we see, of our ancient civilization at present, were all the result of archaeological research.

This article series would sum up some of the most important events in the journey of Sri Lankan Archaeology, milestones which changed the way we think of the past, the way we know the past and the way we see and protect the past. Milestones in Sri Lanka archaeology would include important discoveries to institutional and policy establishments, which, has helped the field to progress to the present and helped expand our understanding and protection of the past. Each article would feature three milestones typically in chronological order. This article would feature:

- Translation of the ‘Mahawamsa’

- ‘Ancient Inscriptions of Ceylon’ 1883

- Discovery of the first stone tools and the establishment of a prehistory in the island

Translation of the ‘Mahawamsa’

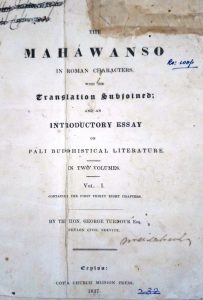

The Mahawamsa is one of the oldest continuously recorded chronicles in the world covering a period of over twenty three centuries; it records a continuous political and religious history of the island from the arrival of Vijaya to the fall of the island to the British. As a historical work, it is of immense value in understanding our past and has aided the historian and archaeologist greatly in his/her study. However, this chronicle was all but forgotten in the 19th century until an accurate translation was made in 1837 by George Turnour, which opened the doors to the study of both the history of Sri Lanka and India.

With the colonization of most of the Indian subcontinent by the beginning of the 19th century, European scholars began to explore the history of the cultures of the Indian subcontinent, like wise Ceylon was no exception. To European scholars, prior to the 1830s, it was believed that the island was devoid of any literature of historical interest, this view was carried forward by the Portuguese historians as well as the early British; Robert Percival in his book in 1803 states “the wild stories current among the natives throw no light whatever on the ancient history of the island. The earliest period which we can look for any authentic information is the arrival of the Portuguese under Almeida in 1505” and John Davy in his book in 1821 mentions “the Singhalese possess no accurate record of events; are ignorant of genuine history, and are not sufficiently advanced to relish it”.Â

This view was all changed with the ‘discovery’ and translation of the Mahawamsa in 1837 by George Turnour. However, Turnour weren’t the first to ‘discover’ the text or even translate it.  Sir Alexander Johnston during his tenure as Chief Justice of Ceylon (1805-1819) had collected various manuscripts of Pali and Sinhalese from temples throughout the country which also included manuscripts of the Mahawamsa, Rajaratnakaraya and the Rajavaliya. These texts were translated to English by Edward Upham with the assistance of the native chief of the cinnamon department who was an authority in Pali and the Wesleyan missionary Rev. Fox; into the work known as Sacred and Historical Books of Ceylon: Also, A Collection of Tracts Illustrative of the Doctrine and Literature of Buddhism, published in three volumes in London in 1833.

But it is the translation of George Turnour that is most remembered due to the fact that Upham’s translation contained many inaccuracies. Turnour in his introduction of his translation states his endeavor was to “account for one of the most extra-ordinary delusions perhaps, ever practiced on the literary world,” and on the other, to prevent these erroneous representations of the “Sacred and Historical Books of Ceylon to be works of authority.”

George Turnour was an oriental scholar who served in the Ceylon Civil Service and it was during his tenure as Asst. Government Agent of Sabaragamuwa (1825-1828) in 1826 that he came across the rare text of the Mahawamsa. Turnour, who was pursuing his studies into the Pali literature of the island with the assistance of a learned Monk named Gallē, came to know of the existence of a continuous written chronicle on the history of the island. He obtained the manuscript  in 1826 from the Mulgirigala Viharaya in Tangalle which was ‘tika’ or a running commentary of the Pali work known as the Mahawamsa, which contained a continuous written history of the island from 543 B.C. To 1758 A.D. Coming to know the importance of this work, he dedicated his life from then on to the translation and dissemination of this material, which brought to light the unknown history of the island. It is stated that due to his official duties the translation was delayed and when he learned of the translation and publication of Upham, he was glad, but soon found that translation to be faulty.

In 1833 he published a paper titled ‘Epitome of the History of Ceylon’ in the Ceylon Almanac which he listed down the succession and genealogy of 165 Kings from the arrival of Vijaya to the British, based on his study of the Mahawamsa and other materials. According to Tennent “in this work, after infinite labour, he succeeded in condensing the events of each reign, commemorating the founders of the chief cities, and noting the erection of the great temples and Buddhist monuments, and the construction of some of the reservoirs…he thus effectually demonstrated the misconceptions of those who previously believed the literature of Ceylon to be destitute of historic materialsâ€.

His translation of the main text from Pali to English was published titled ‘The MahÄwanso, in Roman Characters with the Translation subjoined; and an introductory essay on Pali Buddhistical Literature’, published by the Cotta Church Mission Press in 1837. This goes as volume I and contains chapters 01 to 38 ending with the reign of King Dhatusena. Volume II of George Turnour’s Mahawama was published only in 1889 which was translated and edited by L. C. Wijesinghe as Mahawamsa Part II.

The first Sinhala translation of the Mahawamsa was undertaken by Hikkaduwe Sri Sumangala Thera and Don de Silva Batuwanthudawe between 1877-1883. Subsequently many critical editions have since come about.

By the early 20th century the Government of Ceylon was in wanting of an official English critical translation of Turnour’s Mahawanso; this they found in the person of Prof. Wilhelm Geiger. Prof. Geiger had made a critical translation of this into German in 1908 which was published by the Pali Text Society and subsequently with the assistance of Dr. Mrs. Mabel Haynes Bode; it was translated to English with Prof. Geiger revising the English translation. This critical edition of the Mahawamsa was published in 1912 and remains to date the official translation of the work in English. However Prof. Geiger through his studies had divided the Mahawamsa into two parts, Chapters 01 to 37 he termed the Mahawamsa of which was published in 1912, and from chapters 38 to 101 he termed the Culawamsa which he once again divided as Culawamsa part I and Culawamsa part II, and were published only in 1930.

As mentioned above, at the beginning of the 19th century a detailed history of Sri Lanka before the colonization was unknown to the European scholars and the populace at large. With the fall of the Kandyan kingdom in 1815 and the subsequent decline literature, historical texts of Pali and Sinhalese which were with the Buddhist monks were soon forgotten, having been locked up in Buddhist temple libraries; and it is stated that when Turnour came across it, hardly a Monk knew of its existence. Subsequently with its accurate translation in 1837 by Turnour, a path was created for scholars to explore the island’s past and to know of the people and rulers who shaped Sri Lanka’s ancient Sinhalese civilization.

The translation of the Mahawamsa from Pali to English came in a time when even mainland India lacked a continuous written historical literature and was therefore a major leap forward in deciphering the history of India. It was from the Mahawamsa that the identification of Devanampiya Raja of the Indian inscriptions as Dharmasoka was arrived at, and the subsequent chronology of the predecessors and successors of Dharmasoka were calculated based on the dates of the Mahawamsa. Hence the translation of the Mahawamsa not only unlocked doors in the Sri Lankan context in understanding its past, but also for the south Asian region as well.

‘Ancient Inscriptions of Ceylon’ 1883

Epigraphical data is an important tool in archaeological research. A main mode of communication in the ancient world was through inscriptions, and in the Sri Lankan context, there are thousands of inscriptions from ancient times inscribed on rock surfaces, stone slabs, stone pillars, and caves on various topics of secular and religious nature. The study of epigraphy in Sri Lanka has greatly aided in the authentication of the literature works such as the Mahawamsa and continues to shed light on subjects of social nature not found in the ancient books. As such, the identification of the inscriptions, the deciphering of the text, the translation and publication of the text is of utmost importance for the students of both history and archaeology. Hence the first publication on inscriptions (and the forerunner for major works such as Epigraphia Zeylanica) was a major leap forward and deserves a special place in the progress of archaeology in Sri Lanka.

The story on of the publication of ‘Ancient Inscriptions of Ceylon’ in 1883 dates back to the year 1874, when on request of the British colonial Government, Dr. P. Goldschmidt was appointed to look into the various inscriptions reported throughout the island. He began his work in 1875 starting from the Anuradhapura district and published his first report on 2nd September 1875. This report, also published in the Indian Antiquary, V, contains details of inscriptions within the Anuradhapura town and immediate neighborhood, especially Mihintale. His second report came out on 6th May 1876 and deals with the same material but in a more careful and accurate manner. He soon began to distinguish ancient from modern inscriptions based on paleographical reasons and was able to read and translate them. Dr. Goldschmidt moved on to Polonnaruwa and from thereon searched the districts of Trincomallee, Batticaloa, and Hambantota, writing his final report on 11th September 1876 from Akurasse, before his untimely death in May 1877.

Dr. Edward Muller was next appointed in the beginning of the 1878 to continue the work of Dr. Goldschmidt. He first began the unfinished work of the former in Hambantota and subsequently toured the districts of Anuradhapura, Kurunagala and Puttalam.  Under his supervision, in Polonnaruwa, inscriptions were photographed but the ones not possible to photograph, transcripts were made instead. His attention was chiefly to the inscriptions up to the 13th century; this being due to the fact of them being of philological and historical interest as he considered the ones after the 13th century more of modern period as the language was similar to the present. He finally completed the surveys and compiled the first published book on ephigraphical records in the island titled ‘Ancient Inscriptions of Ceylon’ in 1883 published in London. The book is divided into three parts:

1st part – text and translations of caves and smaller rock inscriptions

2nd part – text of all the longer rock inscriptions as well as pillar and slab inscriptions.

3rd part – translations of text of the 2nd part.

It contains over 200 inscriptions with a systematic explanation of the language of the inscriptions in the introduction.

Discovery of the first stone tools and the establishment of a prehistory in the island

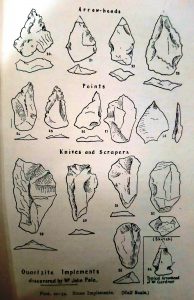

The story of prehistoric man and his environment in Sri Lanka as we know today derives totally from archaeology. One of the main sources of our study of prehistoric man is the stone tools he left behind. And it is the discovery of such stone tools that became the key to the door of Sri Lanka’s prehistoric studies and most importantly, it gave life to the idea of the existence of a Stone Age in the island. Two persons are credited with the discovery of such stone tools; they are Mr. E. E. Green and Mr. J. Pole.

The story of prehistoric man and his environment in Sri Lanka as we know today derives totally from archaeology. One of the main sources of our study of prehistoric man is the stone tools he left behind. And it is the discovery of such stone tools that became the key to the door of Sri Lanka’s prehistoric studies and most importantly, it gave life to the idea of the existence of a Stone Age in the island. Two persons are credited with the discovery of such stone tools; they are Mr. E. E. Green and Mr. J. Pole.

Surface collections of stone tools made of quartz and chert were first discovered by Mr. E. E. Green and Mr. J. Pole in 1885, the latter finding from the vicinity of Maskeliya, and the former from Peradeniya and Nawalapitiya. According to Pole in his 1907 article to the Journal of the Ceylon branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, he states that flakes from all parts of the island, from Puttalam, Hambantota, Nawalapitiya, Matale, Dimbula, Dikoya, and Maskeliya were subsequently discovered and were initially thought to belong to the Neolithic age.

In his article J. Pole states “we merely summarize the uses they were put to: the peeling of the arrow-wands, and scraping of the bow into shape, and shafts of spear or javelin, the skinning of the slain animal and dressing of the skins for raiment, manufacture of bags for porterage of their stone implements, etc.â€

Initially the authenticity of these finds were held in doubt by the academics; but it were the investigations of the Sarasin brothers, the Swiss anthropologist duo that studied the anthropology and ethnography of the Veddas, who in 1907 confirmed these stone tools to be the works of prehistoric men. The Sarasin brothers who explored the Uva Province in the 1890s found similar stone artefacts mostly from the Nilgala caves but they were themselves doubtful of its status. In 1903 they excavated the Toala tribe caves in the island of Sulawesi in Indonesia, where they encountered similar stone artefacts which confirmed to them the artefacts found from the Nilgala caves were indeed stone tools. Subsequently they arrived in the island once again in 1907 and after examining their findings as well as those of J. Pole’s, they concluded that they were made by prehistoric Veddas and belonged to the Paleolithic age.

The next article in this series would feature the Rediscovery of Sigiriya, establishment of the Ceylon Archaeological Survey and H. C. P. Bell’s ‘Kegalle Report’ of 1890.

Â

This is a fantastic article! It gives a well detailed explanation of each milestone while also being concise, such an enjoyable read. The author’s passion for the subject is really reflected here, which makes this article so worth reading.

Dear Ranuli,

Thank you very much for your wonderful comment.

Cheers,

Dear Chryshane Mendis,

I am french and I am in Sri Lanka every 6 months ( I have lodge in Sigiriya ). I am member of french Laboratoire ARAR UMR 5138 , and of Société Française Préhistorique and member of European AARG ( Aerial Archaeology Research Group ). I have very high interest for your research in Sri Lanka. I am working on ” cup stones ” and I know that you have fews in Sri Lanka. Please send me your phone, next time in Sri Lanka ( after coronavirus..) I want to meet you. If you have more informations , do no hesitate to send at my email : alain.bliez@wanadoo.fr.

I hope to hear from you soon, best regards. Alain Bliez France

Dear Mr. Bliez,

Thank you for this interesting comment. I shall contact you via email.

Best regards,

Chryshane