By Chryshane Mendis

This article series would sum up some of the most important events in the journey of Sri Lankan Archaeology, milestones which changed the way we think of the past, the way we know the past and the way we see and protect the past. Milestones in Sri Lanka archaeology would include important discoveries to institutional and policy establishments, which, has helped the field to progress to the present and helped expand our understanding of the past.

The previous article dealt with the milestones of the Translation of the Mahawamsa, the publication of Ancient Inscriptions of Ceylon in 1883 and the Discovery of stone tools in the island. This article would feature:

- The re-Discovery of Sigiriya

- Establishment of the Ceylon Archaeological Survey in 1890

- H. C. P. Bell’s ‘Kegalle Report’

Â

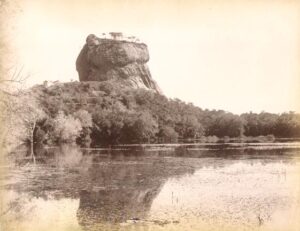

The re-Discovery of Sigiriya

Sigiriya, the 5th century AD rock fortress cum city of King Kasyapa I which traces its hum an occupation to prehistoric times, was after the death of the King, converted into a Buddhist monastery which continued till about the 12th century AD. Afterwards, the architecturally, artistically and technologically stunning remains we see today faded away from history and were consumed by the jungles. Sigiriya is only mentioned once by local sources in the Mandarampura Puvata of the 17th century which describes the settling of South Indian Saivites by King Rajasinghe I, and once again falls into obscurity until the adventuring British explores of the 19th century brings this lost city into light.

an occupation to prehistoric times, was after the death of the King, converted into a Buddhist monastery which continued till about the 12th century AD. Afterwards, the architecturally, artistically and technologically stunning remains we see today faded away from history and were consumed by the jungles. Sigiriya is only mentioned once by local sources in the Mandarampura Puvata of the 17th century which describes the settling of South Indian Saivites by King Rajasinghe I, and once again falls into obscurity until the adventuring British explores of the 19th century brings this lost city into light.

As Sigiriya is mentioned in the Mandarampura Puvata of the 17th century, there is no doubt that the locals knew of this ancient complex, but it was the writings of the British explorers that brought Sigiriya into the light of common knowledge and the academic sphere. Thus, on these grounds, the first person credited with the rediscovery of Sigiriya is Major Forbes of the 78th Highlanders in 1831. Publishing in 1840 in his work titled ‘Eleven Years in Ceylon, comprising sketches of the Field sports and Natural history of that Colony and an account of its History and Antiquities’ he describes two expeditions to Sigiriya in 1831 and 1833. In 1831 he explored up to the base of the rock on the western side and climbed up to the gallery level (mirror wall). In his own words:

“From the spot where we halted I could distinguish massive stone walls appearing through the trees near the base of the rock, and now felt convinced that this was the very place I was anxious to discover…to form the lower part of the fortress of Sigiri many detached rocks have been joined by massive walls of stone, supporting platforms of various sizes and unequal heights, which are now overgrown with forest-trees. Having surmounted these ramparts, we arrived at the foot of the bare and beetling crag; and perceived at a considerable distance overhead, a gallery clinging to the rock, and connecting two elevated terraces at opposite ends, and about half the height of the main column of rock. These remains were very different from anything I had expected to discover; not merely from their remarkable position and construction, but as being the only extensive fragments of the ancient capitals of Ceylon which are neither shrouded by vegetation nor overshadowed by the forestâ€

In 1833 he returned to Sigiriya and explored the area north of the rock towards Pidurangala and traced the ramparts and moat as well as again the gallery or the mirror wall and also the Sigiri tank to the south of the rock. He traced the section which ascends the summit in the north but never attempted to scale the rock due to the great rick involved and added by the discouragement by the local people on summiting the rock due to the area being infested with bears and leopards. In his own words:

“I returned to Sigiri in 1833, and ascertained that the town lay around the palace to the north of the rock, and traced for some distance a stone wall and wet ditch with which it had been surrounded. I then learned that from the highest terrace many small steps leading to the summit of the rock may still be perceived; but in much too dilapidated a state, and in too hazardous a position, for one to attempt… on my second visit I remarked that the projecting rock above the gallery, at least so much of it as is within reach, had been painted in bright colours, fragments of which may still be perceivedâ€

In this initial exploration of the rock, it can be found that the famed Sigiri frescos, the Sigiri graffiti, the water gardens and the lion’s paws were yet to be discovered. The first record of summiting the rock was in 1853 by two young civil servants, A. Y. Adams and J. Bailey. Later in 1875 T. W. Rhys Davids in an article writes how he explored the site and describes how he saw the paintings on the western face of the rock through a telescope. The following year T. H. Baleskey published a much detailed paper on the remains of Sigiriya which describe the gallery, the fresco pocket and other prominent features such as the rampart and moat and also includes the first plan of the ruins of Sigiriya which were visible back then. In 1889 A. Murray of the Public Works Department under the advice of former Governor Sir William Gregory managed in scaling up to the fresco pocket and sketched out thirteen figures.

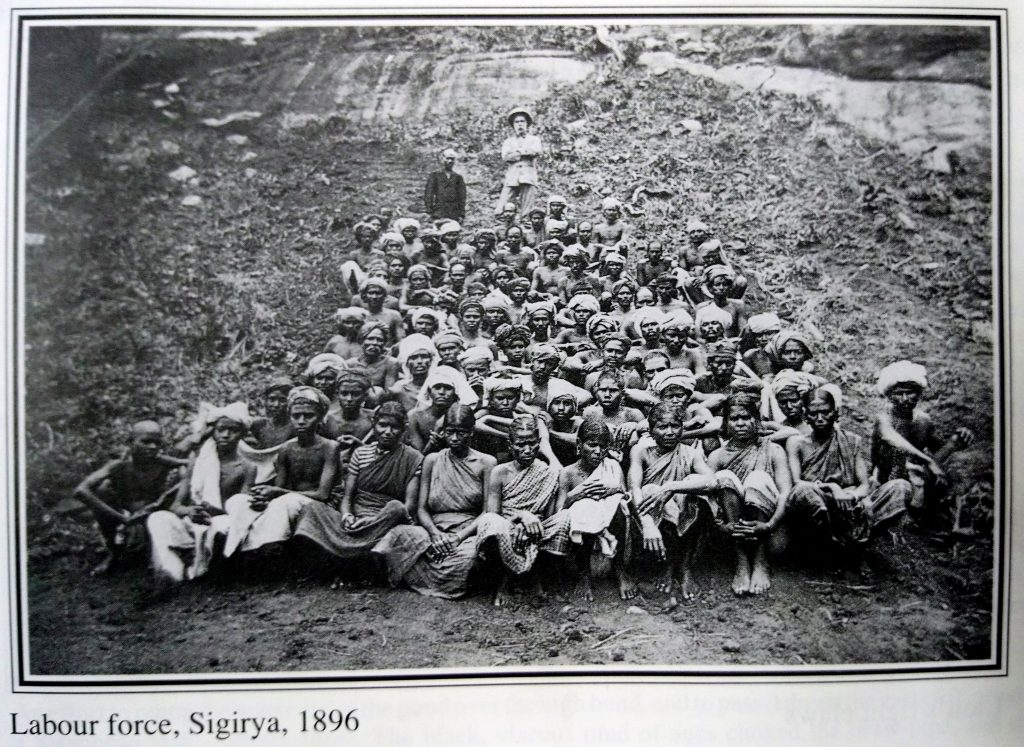

Systematic archaeological excavations began only in 1895 under the leadership of the first Archaeological Commissioner Harry Charles Purvis Bell. The site was explored by Bell on 15th and 16th April 1894 including the summit, which was ascended using jungle ladders. By the end of the year iron ladders had been fixed to ascend the summit and some clearing had begun in preparation for a full season’s work the following year. Work began in January 1895 and lasted till May. During the first four seasons from 1895 to 1898 generally taking place during the first several months of the year, the entire rock and its immediate surroundings were cleared and surveyed, which by the 5th season in 1899 extended to the surrounding sites of Mapagala and Pidurangala. Excavations were initially begun on the summit and beneath the western scarp in 1895 but from the following year till 1897 all excavations were concentrated on the summit. During the excavations of the summit in 1896, apart from revealing the ruins, systematic trenches were opened in order to study the foundations of the walls; and again in 1898 shafts were driven to the bedrock of the summit to further study the foundations which revealed an underground drainage system. In the seasons of 1896 and 1897 all 22 frescos were systematically studied and copied in oil paint.

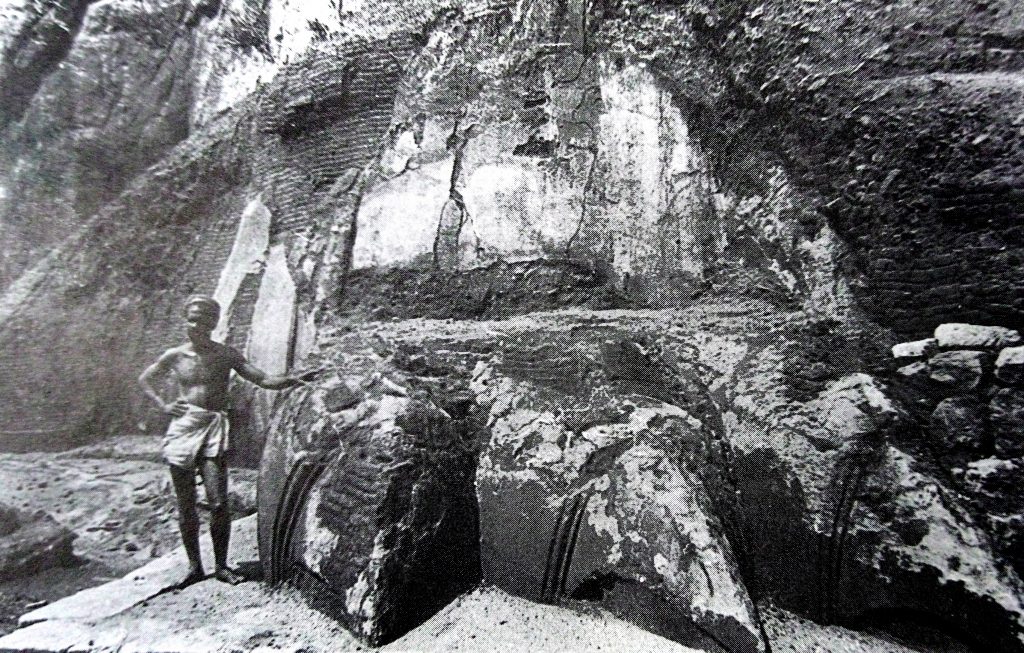

In the initial archaeological excavations in Sigiriya, one of the most stunning discoveries took place in 1898. Up until then, although the name of Sigiriya implied ‘Lion Rock’ no trace of a lion had been found, neither in painting nor in sculpture, which confused scholars on the origins of its name. That is until H. C. P. Bell began excavation of the ‘maluva’ or terrace to the north of the rock from which the final ascent to the summit is. At the base of the rock from where the upper gallery to the summit would have started was a mound from where the ladders were placed to ascend the summit; this was thought to be a mound of debris from when the upper gallery had fallen off. But the mass proved to be solid brick work and in the center the flight of stairs were found. This discovery is best described in Bell’s own words from the Annual report of that year:

“When following the curved ground line of the north façade to the massive brick structure, s0me stucco-covered work was uncovered. This at first seemed to represent very roughly moulded elephant heads – three on either side of the central staircase – projecting from the brick work in high relief, life size. Closer examination and the presence of a small boss further back than the ‘heads’ gave the clue to a startling discovery – the most interesting of many surprises furnished during the four season’s work at Sigiriya. These alto relievos were not a variant form of the ‘elephant-headed dado’ of the chapel ‘screens’ of the larger dagabas of Anuradhapura. They were none other than the huge claws – even to the dewclaw – of a once gigantic lion, conventionalized in brick and plaster, through whose body passed the winding stairway, connecting the upper and lower galleries…towering majestically against the dark granite cliff, bright coloured and gazing northwards over a vista that stretches almost hilless to the horizon, must have presented an awe inspiring sight for miles around. Thus was clinched forever to the hill the appellation Sihigiri “Lion Rock.â€â€¦here then is the simple solution of a crux which has exercised the summaries of writers – the difficulty of reconciling the categorical statement of the Mahawamsa and the perpetuation to the present day to the name “Singha-giri†(Sigiri) with the undeniable fact that no sculpture or paintings of lions exist on Sigiri-galaâ€

By the beginning of the 20th century, much of what we know of Sigiriya had been revealed, properly surveyed and excavated, but the enchanting place still continued to reveal its secrets in the 20th century and even in the present. Thus the rediscovery of the fortress city and its total revelation served as a laboratory for the discipline and a huge step in the initial years of archaeology in Sri Lanka.

Establishment of the Ceylon Archaeological Survey in 1890

Archaeology as a professional discipline began only in the early 19th century and by the mid-19th century had found its way to Sri Lanka with the British administration taking a keen interest in the ruined monuments found throughout the island, especially in the North Central Province. In 1868 Governor Sir Hercules Robinson appointed a committee to look into the ancient monuments in the island and by the early 1870s photographs and preliminary site surveys had been carried out in Anuradhapura. Until 1890 irregular investigations were conducted into the ancient monuments of the island such as the epigraphical survey carried out between 1875 to 1879 which led to the publication of the major work ‘Ancient Inscriptions of Ceylon’ in 1883 and an archaeological survey under S. M. Burrows between 1884 to 1886 in Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa. During this particular survey, the area around the major monuments in Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa were cleared of the jungle and a surface search for monuments was carried out in and around the major sites; also old roads were cleared and new roads constructed to the larger ruins as well as the drawing of schemes for further excavations.

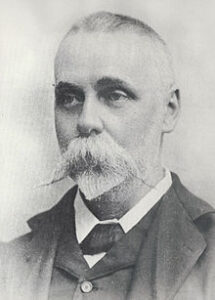

The proper establishment of a Government department for Archaeological work was started in February 1890 with Harry Charles Purvis Bell as its first Commissioner. His first assignment was a survey of the antiquities of the Kegalle District of which he was the District Judge; this survey produced the important work known as the ‘Kegalle Report’ (described below). After this preliminary survey of the Kegalle District, he was given the option of Tissamaharama or Anuradhapura for a major scientific investigation, which he chose Anuradhapura and proceeded to on the 7th of July 1890 – this date is thus considered the founding date of the Archaeological Survey of Ceylon and the birth of scientific archaeology in the island.

Bell started off his work in Anuradhapura with just a Labourer supervisor and 20 labourers, which was fondly known as ‘Bell’s Party’ and a systematic exploration of the jungle was carried out to determine what ruins lay above ground. Explorations were done in the modern town of Anuradhapura and immediate surroundings and were divided into 9 areas for ease of exploration. In 1893 archaeological work was extended to the Sabaragamuwa Province and to the Central Province the following year. During its initial years till the turn of the 20th century exploration, excavation and conservation work were centered primarily on the sites of Anuradhapura, Polonnaruwa and Sigiriya. The Archaeological Survey of Ceylon was at a later date named the Department of Archaeology of Sri Lanka and continues to be the governing authority on the archaeological heritage of the island. Thus the establishment of an official governing body for the archaeological matters in the country was a major milestone in the expansion of the discipline of archaeology in Sri Lanka.

Â

H. C. P. Bell’s ‘Kegalla Report’

Interest into the archaeology of the island was shown by the British from early on and several sporadic efforts were made into the study from the 1870s; it was finally in February 1890 that the Archaeological Survey of Ceylon was begun with Harry Charles Purvis Bell as the first Commissioner. At the time of commencement, Bell was serving in the Kegalla district as District Judge, and hence his first assignment was the survey of his resident district which comprised of the ancient divisions of the Four Korales (Sathara Korale), Three Korales (Thun Korale) and Lower Bulatgama (Pata Bulatgama). This report which comprised of an intense historical and archaeological survey was thus the first official work of the Archaeological Survey of Ceylon (which later became the Archaeological Department).

The title of the report goes as ‘Report on the Kegalla District of the Province of Sabaragamuwa’ and was first published in the Sessional Paper XIX – 1892: Archaeological Survey of Ceylon having been printed by George J. A. Skeen, Government Printer, in 1904. The work is structured into three Parts, and is best explained in Bell’s own introduction as follows:

“The present report has been arranged under four heads. The ‘Introduction’ deals with the historical geography of the Kegalla District. In Part I. (Historical) is recorded so much of its history as I have been able to glean from records, chiefly from the fifteenth century onwards. Part II. (Antiquarian) sums up briefly the characteristic forms of architecture and temple adornment in the District, and gives in some detail description both of ancient sites, legendary, and historical, and of the more important vihares, dewales and kovils of each Korale and Pattuwa. To Part III. (Epigraphical) has been left the treatment of all stone inscriptions and copper-plate or palm-leaf (ola) grants discovered in the course of research. finally, in the ‘Appendices’ will be found miscellaneous information bearing on the District which would have been out of place in the textâ€.

In Part I, he discusses the historicity of the district from ancient times unto the present. However the most important sections of the work are Parts II & III. Part II which deals with the antiquity of the district, although according to Bell’s own words, the Kegalle district is somewhat barren in terms of archaeology, the largest category of monuments recorded is religious establishments, a significant number of which traces its history to the Anuradhapura period. Part II opens with a general categorization and introduction to the monuments found, dividing them as Temples (cave temples and detached buildings), Viharas, Dagabas, Bodhi-maluvas, Dewales, and Architecture, Sculpture and Painting. From then on, the content is divided by the Korale, Pattuwa and finally by the Village in which is given a clear description of the antiquities, its location, present state with measurements and historical quotations from various sources to supplement the description. Apart from the many religious monuments described, there is recorded also other secular monuments such as the Manikkadawara fort, Balana fort and Peradeni Nuwara ruins.

Part III gives detail on the epigraphy of the district, dividing into Inscriptions, Sannas and Treasure and Boundary marks. Several early Brahmi cave inscriptions are described along with inscriptions dating from the 5th, 10th, 11th centuries all the way to the 19th century with the slab inscription of King Sri Vickrama Rajasinghe of 1806 in the Selawa Viharaya.

Many Sannas belonging to Viharas, Dewalas and private individuals too are recorded with the majority being written on copper plates. The oldest Sannas recorded is belonging to King Buvenekabahu V. Few locations of treasure marks and boundary marks too are given.

In the Appendices, the following details are supplied; Constitution of the Kandyan Kingdom with the Four Korales in particular, Lists of villages held under different Tenures, Lists of Registered Service Villages appertaining to different Temples, Lists of Vihares, Devales and Kovils, Flags of the Disavas and other Kandyan Officials, Cartography of the Kegalla District and some Boundary Ballads.

The significance of this work lies not only in the fact that it being the first project of the Archaeological Survey but also as a comprehensive record of the monuments of that district as they were during the late 19th century. It serves at present as an important source document for any archaeological or historical research conducted within this area; also since much of the archaeological data given in the report mainly concerning the secular monuments have since vanished, this serves as one of the only records of these ruins in a systematic way (e.x:- the Balana kadawatha described in the report can no longer be seen and is the only description available of it).

We celebrate the achievements of Bell and others in reconstructing Sigiriya. No doubt it was praiseworthy and we are grateful. However, many poor Indian Tamils in the labour force had helped him and worked under most difficult circumstances and many must have perished? Who will recognise and appreciate their contribution? How ungrateful we are.

Dear Udage,

I am HCP Bell’s great-grand-daughter, and I also lived in Sri Lanka for three years, between 1988 and 1992. Whilst I am very proud of what my great grandfather achieved on the island (which I think has benefitted all of Sri Lanka because of the impact those archeological sites has had on the tourist industry for one, and also because of the important discovery of much of the island’s history), I am also very aware of those who suffered under his rather stern leadership as Archeological Commissioner. It was a very different time, and things were done which were considered acceptable then, but please may I sincerely apologise on behalf of all my family for any suffering that was caused.

I have a great love for Sri Lanka and its people, and I will be coming, with my brother and my father (who is HCP’s grandson, and who also lived in Ceylon as a child) to visit just before Christmas this year, in part to return a small statue to the Temple of the Tooth, which we believe my great grandfather removed and gave to his daughter-in-law (my grandmother) many years ago.

If you or any of your family would like to meet with us, so that we can express our thanks and apologies in person, please let me know by replying here.

I greatly enjoyed reading this article by Anuradha, and thank him for such a succinct explanation.

Best regards,

Fiona Davis (nee Bell)

Thanks for the very useful and interesting article.

i am a senior journalist with a love of archaeology and history and I must again congratulate for their seminal work in popularising Sri Lankan historical research. It is a task that is crucial to tear away the cobwebs of purely superstition and folklore-based understanding of Sri Lankan history among the mass of people. I especially congratulate Chryshane Mendis for his meticulous archaeological journalism – a rare skill in any language in this country. ‘archaeology.lk’ is making history in this pioneering popular documentation of local archaeological research. I also appreciate the clarifications made by a descendent of the great H.C.P. Bell. But she need not apologize at all for any wrongs by her forebears. No one can be responsible for things done by previous generations of the remote past. Bell, like all early archaeologists, was naturally primitive in his methods which resulted in as much destruction of ancient artifacts as there was preservation. This happened in Babylon, Mohenjodaru and numerous other ancient sites across the world. We Sri Lankans have been far more careless in more recent times in destroying our heritage for modern utilitarian purposes. Best wishes to Mendis and the team at archaeology.lk.

May the curse of the damage he did to our country fall on the descendants of hcp bell. Not only the history of Sri Lanka was completely distorted and a separate history was written, but the treasure of Sigiriya was also looted by the white man. May they be cursed!