By Chryshane Mendis

Introduction and geographical position

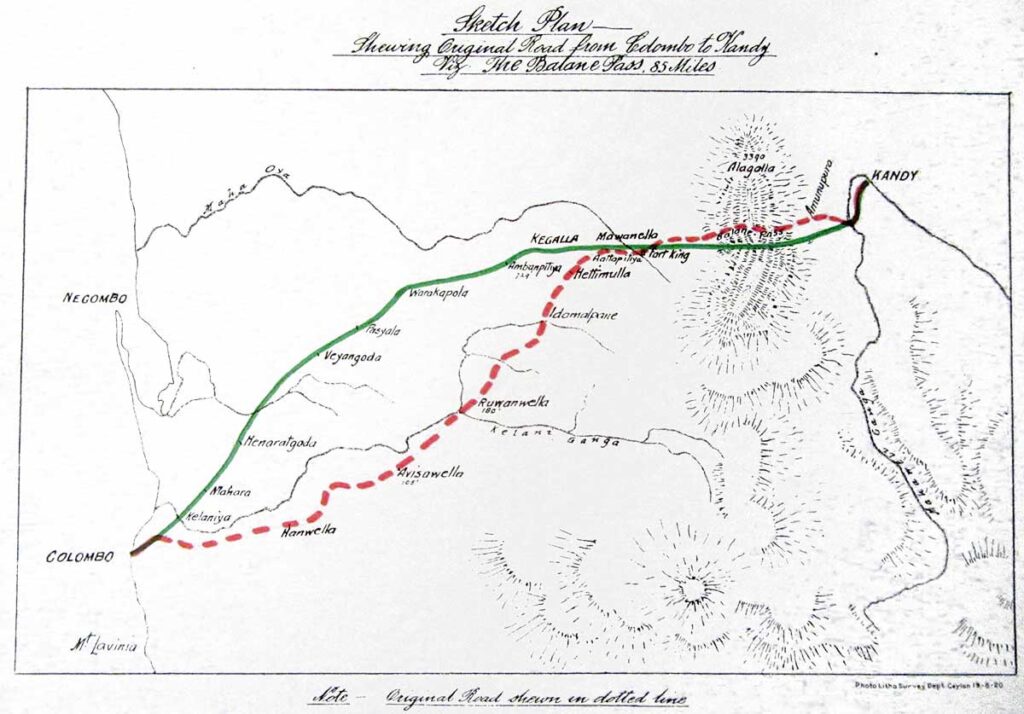

The Balana pass, the key to the Kandyan Kingdom was a pass on the southern edge of the Alagalla Mountain range from which ran the old Colombo Kandy road giving access to the mountain kingdom. This was the most important pass in the Kingdom with the other being at Galagedara, as the road coming from the lower plains climbs over a thousand feet in less than a mile over the pass to the plateau of the central highlands. The hill of Balana, being over 600m (GPS – N 7° 16.18116, E 80° 29.77146) above sea level, fell under the ancient administrative division of the Four Korale (Sathara Korale) in the Galboda pattuwa. Balana is mentioned in the Trisinhale Kadaim Potha as being the boundary line which separated the Four Korales from the Uda Rata, and the maintenance of this post fell onto the Dissave of the Four Korales. Today Balana falls under the Central Province and is the also the boundary line between the Sabaragamuwa and the Central Provinces. Balana was a key point in the old road to Kandy (From Colombo via Kotte and Kaduwela to Sitavaka, Ruwanwella, Arandara, Attapitiya, Ganetanna and over Balana to Gannoruwa) which many a foreigner had written about its difficult climb.

The Balana pass, the key to the Kandyan Kingdom was a pass on the southern edge of the Alagalla Mountain range from which ran the old Colombo Kandy road giving access to the mountain kingdom. This was the most important pass in the Kingdom with the other being at Galagedara, as the road coming from the lower plains climbs over a thousand feet in less than a mile over the pass to the plateau of the central highlands. The hill of Balana, being over 600m (GPS – N 7° 16.18116, E 80° 29.77146) above sea level, fell under the ancient administrative division of the Four Korale (Sathara Korale) in the Galboda pattuwa. Balana is mentioned in the Trisinhale Kadaim Potha as being the boundary line which separated the Four Korales from the Uda Rata, and the maintenance of this post fell onto the Dissave of the Four Korales. Today Balana falls under the Central Province and is the also the boundary line between the Sabaragamuwa and the Central Provinces. Balana was a key point in the old road to Kandy (From Colombo via Kotte and Kaduwela to Sitavaka, Ruwanwella, Arandara, Attapitiya, Ganetanna and over Balana to Gannoruwa) which many a foreigner had written about its difficult climb.

[porto_blockquote footer_before=”Percival” skin=”primary”]”very difficult…narrow intricate paths…steep ascents and descents…extremely fatiguing”[/porto_blockquote]

[porto_blockquote footer_before=”Macpherson” skin=”secondary”]”by far the most difficult track of a journey I ever saw, having to scale numerous almost perpendicular rocks”[/porto_blockquote]

[porto_blockquote footer_before=”Mahony” skin=”tertiary”]”This mountain exceeds steepness and wilderness any as I have yet met within India”[/porto_blockquote]

Are some of the comments on the pass as mentioned by Major R. Raven-Hart in his work the Great Road. This toilsome climb up the pass was rewarded with the stunning view of the western horizon. Balana which means the Look-Out in Sinhala was thus used as a sentry point on the approach to Kandy and as a strategic position in defence from invasions. The position was fitted with a fort to check enemy advances, the remains of which can still be found on the summit. The path behind the Balana railway station is said to be old road which runs a steep 2.5km climb to the summit of the mountain and from there on runs relatively flat to the open plains towards Danture. The path now is well carpeted and has a considerable built up neighbourhood including a bus service from Kadugannawa; hence it is hard to imagine the toilsome climb one would have had to endure 300 years ago. The summit of Balana gives a commanding view of the surroundings and one truly needs to be there to experience its strategic importance which words can not describe.

[wpgmza id=”4″]

Balana Fort on Google Maps

Google Street View 360 image of Balana Fort

Historical background

As per a survey of the writer, the first mention of Balana in the Sinhalese sources is during the invasion of Kanda Uda Rata by King Rajasinghe I of Sitavaka in 1582. The Rajavaliya notes that King Karaliyadde Bandara, ruler of the hill country was defeated at Balana by King Rajasinghe followed by the subjugation of the entire Kanda Uda Rata under Sitavaka.

The next episode Balana appears is during the last days of the Sitavaka kingdom where Kandy frees itself from the former. The Sitavaka kingdom lost its control over Kanda Uda Rata in the early 1591/92 which the Portuguese soon capitalized by sending an expedition under Konappu Bandara to crown Don Philip or Yamasinghe Bandara as a vassal King in Kandy; but with the untimely death of Yamasinghe Bandara, Konappu Bandara takes control over the kingdom. In 1593 King Rajasinghe invaded the Four Korales in order to regain control of Kandy and sent his general Arritta Kivendu Perumal ahead of a large army to attack the hill country but was prevented from going beyond Balana as it was blocked by Konappu Bandara and the army of the hill country. Seeing this, Rajasinghe himself took command of the army and once again attacked the pass in which he met his Waterloo at the hands of Konappu Bandara; and within less than a year after the battle he died and along with him the Kingdom of Sitavaka as well, marking the beginning of the Kandyan Kingdom as the sole independent Sinhalese kingdom in the island.

In 1594 the Portuguese under Pedro Lopes de Souza launched an invasion of Kandy carrying the Princess Dona Catherina or Kusumasala Devi to be placed on the throne by removing the usurper Konappu Bandara but which ended at their defeat in Danture. This time, there seems to have been no opposition at Balana for the only major source on this expedition, Queyroz, states that apart from fortified stockades and felled trees which were easily overtaken, the Portuguese made a swift climb of this most perilous part of the expedition and adds the victory over Balana as one of the General’s achievements. Here Gaston Perera gives two theories as to why there was no resistance at Balana; one was, the presence of Done Catherina may have changed the minds of the Kandyans to fight or not a force bringing the last relict of their royal line (as Konappu Bandara was not the legitimate ruler), and two, that it would have been part of Konappu Bandara, now known as Vimaladharmasuriya’s overall strategy of drawing the invading force deep within his territory. In the end, it may seem so as after the occupation of the city, with the defection of the Lascorins after the murder of their leader Jayavira, the Portuguese made a retreat back to Colombo but were cut down in the fields of Danture.

The next episode with Balana comes 9 years later in 1603 when under the command of Dom Jeronimo de Azevedo the Portuguese once again attempted to conquer Kandy ending in the Formosa Retirada or the Great Retreat. In the years up to 1603 Vimaladharamasuriya had been buildings a series of fortifications along the passes to the central hills in anticipation for the impending invasion, amoung them was a strong stone fortress of Ganetanne at the foothills of Balana and for the first time, it is mentioned by Queyroz that Balana was fortified with a fort. On previous occasions, the pass in its natural form functioned as a fort and with numerous stockades at narrow gaps as defenses. But under the new defence plan of Vimaladharmasuriya, Balana was equipped with a strong stone fortress. Queyroz gives the following description of it:

[porto_blockquote footer_before=”Queyroz” skin=”quaternary”]“The new fortalice of Balana stood on a lofty hill upon a rock on its topmost peak; and it was more strong by position than by art, with four bastions and one single gate; and for its defence within and without there was an arrayal of 8,000 men with two lines of stockade which protected them with its raised ground, and a gate at the foot of the rock and below one of the bastions which commanded the ascent by a narrow, rugged, steep, and long path cut in the Hillâ€[/porto_blockquote]

It is recorded by Queyroz that the Portuguese took a month in ascending the pass indicating bitter and protracted fighting up the pass as suggested by Gaston Perera. Coming within range of the fort they set up a battery of three artillery pieces on the neighbouring mountain and poured a continuous fire for three days without any effect. Another attempt was made to come up the rear via an Elephant path some two miles from Balana but that too was found defended by the Sinhalese. No direct assault was seen possible due to the steep and rugged nature of the terrain. A Sinhalese appeared to the Portuguese and offered to show another footpath up the mountain which commanded the fort. The Captain Major and 200 selected veterans attempted the climb and as Queyroz gives it “so steep and precipitous that if there had not been the thick rattan which served them as foot hold, it would have been impossible to ascend it, and if any one of them had given way, there was no help but to fall down headlong. They sent the whole night in its ascent†but upon reaching the fort they found it deserted except a few to cover the retreat. Vimaladharmasuriya had resorted to his tactic used in 1594 and which would be characteristic of all future Kandyan operations, which is to strategically retreat allowing the enemy to venture deep into the territory and cut them on their retreat when their supplies run out. The Portuguese thus occupied the fort of Balana and even conducted a Thanksgiving service in the fort. But soon internal dissensions amoung the lascorins made the Captain General realize the grave situation he faced and before long the surrounding hills were full of Kandyans prompting the Portuguese to retreat leaving the stronghold of Balana; and this long retreat to Colombo with the entire lowlands under rebellion is known as the Famous Retreat. Thus although Balana fell to the Portuguese for a short time, it was never conquered militarily.

Once again under the command of Azevedo, the Portuguese in August 1611 launched another attempt to conquer the hills and upon reaching Balana found it abandoned, unlike the stiff resistance it gave eight years earlier. The Portuguese soon occupied it and in a fortnight erected a fortification of wood. This fact is confirmed by the Sinhalese war poem the Rajasinghe Hatana. This expedition which ventured into Kandy was called off by a truce between the two parties but sorties into the Kandyan territory continued for several years without any opposition from the Kandyans. And the Portuguese records indicate that Balana was even occupied for some time from 1615 to 1616. Paul E. Pieris notes that in 1616 Balana was put into good order by the Portuguese by constructing a large tank for the storage of water, clearing the forests around the fort to a distance of a musket shot and the construction of a drawbridge over the moat. The reasons the Portuguese were able to get a foothold at the gates of Kandy may be due to the fact of the weak administration of King Senerat who assumed the throne after the death of Vimaladharmasuriya in 1604 and his policy for peace over war unlike the former who was a battle hardened warrior trained under the Portuguese themselves.

The next encounter comes in the expedition by Diogo de Mello in 1638 which culminated at the battle of Gannoruwa. Here too once again Kandy under the leadership of Rajasinghe II evacuates Balana and the city-based on their famous strategy to draw the enemy deep within and attacks them on their retreat, this time ending at the plains of Gannoruwa and after the battle, the King re-sends troops to keep watch at Balana according to the Parangi Hatana. This is the last instance the Portuguese would be related to Balana as their expulsion from the island comes 20 years later in 1658.

Balana comes into only one military engagement with the Dutch more than a century later. The relative peace which the Dutch maintained with Kandy since the 1640s broke down in the 1760s and war began in 1761 ending in 1766. Towards the end of the war in 1765 the Dutch mounted an invasion to the Kandyan heartland through the usual route of Balana and found the pass and the city deserted in typical Kandyan fashion. The invading force occupied the city for several months but realizing their shortage of supplies decided to retreat back to Colombo but found the Balana pass occupied by the Sinhalese. The following is taken from a correspondence with Batavia (The Dutch Wars with Kandy 1764-1766)

[porto_blockquote skin=”quaternary”]“knowing that the usual pass over the notorious hill was beset with batteries, wolfpits, and other obstacles, they decided on the suggestion of the old Mudaliar Dessa Nayak to make their further retreat along a path until then-unknown to us running along the hill Ballane and over back of this, northwards to come out into the seven korales beyond Weewedeâ€[/porto_blockquote]

The garrison of Kandy finding the Balana pass occupied by the Sinhalese was shown a by-path by the Mudaliyar of the Hapitigam Korale and thus avoided a total massacre.

The Balana pass would face another two military excursions under the British but yet, would be evacuated as per their famous strategy. During the war of 1803, when the British marched up the great road they found the pass to be abandoned. Once again during their final excursion in 1815, the Balana heights were found abandoned on the approach of a detachment under Major Moffatt on the 2nd of February. D’Oyly in his own words states “I sincerely rejoice, that the reputed difficulties of the Balana Mountain have been surmounted with so much Facility, & and that Yatinuwara & the Capital are so fairly open to our Troopsâ€. And with the surrender of the Four Korales under the Adigar Molligoda to the British, the Balana pass as with the rest of the country a few days later came under British dominion thus ending the saga of the Balana pass as the key to the Kandyan Kingdom. And with the building of the new Kandy road in the 1820s, the old road up the Balana pass lost its prominence and was soon a forgotten path.

The Mountain of Balana, the gate way to Kandy as seen above, although defendable, was abandoned most of the time giving entrance to the city. Only twice was an enemy denied access and given battle at Balana, that when the redoubtable Rajasinghe attempted to retake Kandy and when Vimaladharmasuriya checked the Portuguese advance in 1603. These two incidents show the strength of the position if it is defended with determination, but the overall Kandyan strategy meant allowing the enemy access to the city thus abandoning the position at Balana. Further, the ideology of the Kandyans regarding field fortifications were as stated in Channa Wickramasekara’s Kandy at War –“the field fortifications were built more for the purpose of hindering an advance than stopping itâ€.

The Fort: an archaeological analysis

[porto_blockquote footer_before=”H. C. P. Bell” skin=”quaternary”]“The site of the old fort…the villagers call the spot, where it stood, Ukkotu-tenna. Strictly there are two forts, the upper and lower, together covering about three acres, of which the lower fort claims five-sixths. This had been encircled by a stone wall about 4 ft. in thickness, now broken down. The walls of the upper fort are less visibleâ€[/porto_blockquote]

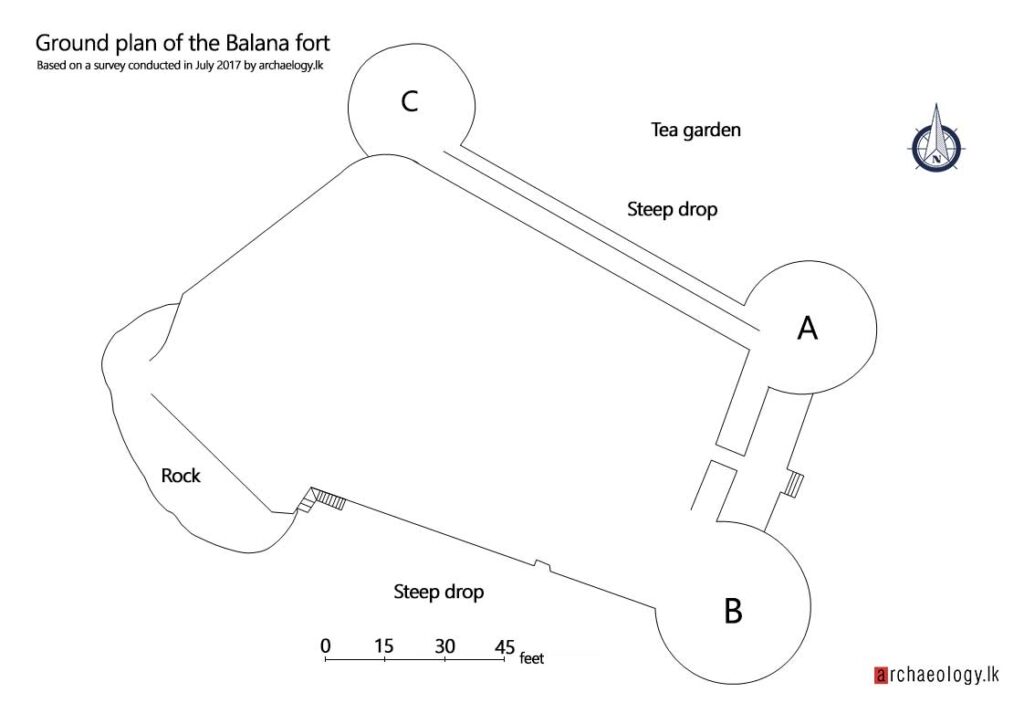

The above is a description of the fort by H. C. P. Bell in his famous Report on The Kegalle District in 1892. As at today, only the upper fort remains. The present ruins of the Balana fort can be found on the summit of the Balana hill overlooking the Balana railway station.  One can access it via the road from the Balana railway station from which it is a 2.5km hike up or from the Kandugannawa Balana road from behind the Kadugannawa station which is about 5km. The access to the fort is through a tea estate with a new board showing the fort. A paved path has been made recently leading to the fort. The present ruins are made of stone and the area is being cleared from time to time although certain sections were hard to access due to the thick thorn bushes. The entrance to the fort is from the southeast and is surrounded by three round bastions. There are two entrances on two levels. The two level entrance is flanked by two round bastions on either side. The first entrance is 2 feet 10 inches wide with a flight of six steps to the first level which is 3 feet 6inches above the ground; the second entrance is 10 feet directly in front of that which is 3 feet wide and rises 4 feet above that level giving access to the inside of the fort. The two bastions from the first level is 37 feet apart and the walls of these entrance features are roughly 1.5 feet thick. The two bastions ‘A & B’ slightly differ in size with the bastion ‘A’ being smaller than the other. The height of the bastions varies as the elevation there changes but not exceeding roughly 4 feet in height. The wall between bastions A and C is roughly 80 feet in length and contains three walls at three different heights. The total width between these three walls is 9 feet.

One can access it via the road from the Balana railway station from which it is a 2.5km hike up or from the Kandugannawa Balana road from behind the Kadugannawa station which is about 5km. The access to the fort is through a tea estate with a new board showing the fort. A paved path has been made recently leading to the fort. The present ruins are made of stone and the area is being cleared from time to time although certain sections were hard to access due to the thick thorn bushes. The entrance to the fort is from the southeast and is surrounded by three round bastions. There are two entrances on two levels. The two level entrance is flanked by two round bastions on either side. The first entrance is 2 feet 10 inches wide with a flight of six steps to the first level which is 3 feet 6inches above the ground; the second entrance is 10 feet directly in front of that which is 3 feet wide and rises 4 feet above that level giving access to the inside of the fort. The two bastions from the first level is 37 feet apart and the walls of these entrance features are roughly 1.5 feet thick. The two bastions ‘A & B’ slightly differ in size with the bastion ‘A’ being smaller than the other. The height of the bastions varies as the elevation there changes but not exceeding roughly 4 feet in height. The wall between bastions A and C is roughly 80 feet in length and contains three walls at three different heights. The total width between these three walls is 9 feet.

Bastion C was covered in thick undergrowth which was hitherto unknown to the writer and thus it was ‘discovered’ during a field survey carried out by the writer and the team in July 2017 when clearing the undergrowth. This bastion appears to be smaller than the other two and is situated above a small drop facing the Balana road. This is at the northern tip of the fort. From here, the wall turns southwest and runs for about 70 feet. This stretch too, the writer had to cut his way through the thorn bushes and hence it was difficult to gauge the height of the wall from the outside; as the entire area within the fort is of the same level as that of the walls. This wall ends at an ‘S’ shape at the edge of a natural rock. Few feet away it begins once more towards the southeast along the rock. From here one could gaze upon the open plains of the Four Korales which is similar to the view from the Kadugannawa climb on the Kandy road. The wall from here, now basically a foundation on top of the rock, runs for 43 feet till the rock ends and furthermore two drains could be seen cutting through the foundations of the wall; the width of the wall is about 4 feet here. From there turning further eastwards runs the wall for about 90 feet to bastion B. At the edge of the rock are a flight of steps to the base of the wall towards the bastion. There are three steps turning in towards the fort and 14 steps running parallel to the wall to the base, from which is a steep drop towards the west with large trees. On this section, the maximum height of the wall reaches 10 feet. Here 10 small drains could be found coming from within the wall. On the 90 feet stretch of the wall towards bastion B, there is a section 30 feet before the bastion which appears to have broken away creating a gap of 5 feet in width and 6 feet in height. The width of the wall on this long stretch is 4 feet. The entire area of the fort is roughly 14,900 square feet and the walls are perpendicular to the ground with only bastions A & B showing a slight angle.

Speaking to the department of Archaeology, they explained that no excavation has been conducted here but said some conservation work had been carried out in the early 2000s, and this was evident as all the remains are in a good state of preservation and in certain sections cement too could be seen used as mortar. At certain places within the fort, broken tiles could be seen indicating that a roofed structure in the center of the fort existed. A proper excavation would be necessary for a deeper analysis of the fortification.

A military perspective

From the remaining sections, it is possible to assume that a garrison of over 100 soldiers would have fitted within the fort. The bastions are not large enough to hold numerous heavy cannons but possibly one large cannon or three to four Kodithuwakku (Gingals-light artillery). The present road runs below bastions A and C and at a particular bend, the road runs less than 100 feet below bastion C. Therefore as this section is exposed to the road, it might be the reason for the extra strengthening of the wall in three lines on this section. Also, the old Kadawatha would have been placed in an area across the present road below the northern section of the fort (this section of the hill north of the fort to the road is in thick jungle, a proper survey would perhaps shed light onto more features connecting the fort to the Kadawatha). Bastion C could have commanded a large area across the road to the neighbouring mountain. The two entrances are designed in a fashion where only one person could enter or exit at a time thus making an entrance to the fort by storming almost impossible. The true topography of the fort has been distorted by the tea plantation making it hard to understand its historical and military context. Further the Kandyans had created an effective communication system from Balana to the Capital; this was by way of beacon signals. When the enemy was sighted, the beacon on the Balana hill and the neighbouring peak would be lit, which would be followed by the lighting of a beacon on Diyakelinawala mountain and from that to the Gannoruwa hill from which would be communicated to the city.

Towards the west of the fort about 100 feet below is an empty land with a rather flat surface with less trees; on our way down to the station we found a footpath just below the fort on the Balana road which led to this land, it was relatively flat with few trees and tea bushes at the beginning of the path. As stated earlier, the fort had two sections, an upper and lower. Clearly the ruins on the summit are that of the upper fort. It may be possible that the lower fort was situated on this location which appears to be larger in area than the upper fort. There were sections of stone walls along the path but those appear to have been put up for the tea plantation. The encroachment of the tea plantations in this lower section as well have rendered it impossible to identify any features as similar sized stone have been fitted as retaining walls for the tea bushes.

Dating the present remains of the fort

Regarding the construction of the Balana fort, in historical literature, the first permanent fortifications appear in 1603 which were built by King Vimaladharmasuriya. Later it is recorded in 1611 that the Portuguese spent a fortnight erecting a fortification of wood. And with their occupation of the fort for a small period, in 1616 it is stated that the Portuguese added modifications to the place. Apart from these, there is no available record to indicate a construction.

The only means of finding an approximate date would be through a proper archaeological analysis through excavations and as well as examination of its features through a comparative analysis. The questions put forward here with regard to the present ruins are, the when and who of its construction? The ‘who’ comes due to the fact that although it is generally known as a Sinhalese fortification, it is a fact that it was occupied by foreigners at certain periods. The main elements drawn from the fortifications for a comparative analysis would definitely be the bastions. What is unique here is that the bastions are round; which is unusual for an artillery fortification.

Regarding the ‘who’ of the construction of the fort, all European artillery fortifications from the mid-16th century no matter how small, adapted the bastion fort design, which was the norm until the mid-1800s. In the bastion fort design, the bastions which were round during the middle ages were made to an angle with two sides and two flanks which removed any blind spots by giving fire cover from any point in the rampart. Thus the use of round bastions fell out of use; even small forts like the Matara Star fort and the Katuwana Dutch fort have angled bastions. Thus it is hard to assume that this is the work of any European power, hence it is more likely a Sinhalese work.

Regarding the ‘when’ of the construction, the last record of construction comes in the early 17th century as stated above. The Dutch nor British spent much time here, and with the fall of the Kingdom to the British, they concentrated on their military outpost at Amunupura a short distance away from Balana. Even during the 1818 rebellion, no record of any activity at Balana was found. Thus it has to be a work before 1815. The question of whether the present remains were constructed in the 1600s or the 1700s could only be confirmed by an archaeological excavation.

References

- Abeyawardana, H.A.P. (1978), A Critical Study of Kada-Im-Pot, Author’s doctoral thesis. Government Printers.

- Bell, H.C.P. (1904), Report on the Kegalle District – XIX 1892. Colombo: Government Printers.

- Codrington, H.W. (1917), Diary of Mr. John D’Oyly 1810-1815. Journal of the Ceylon Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, Vol. XXV.

- Dolapihilla, P. (1959), In the Days of Sri Wickramasingha. Maharagama: Saman Press.

- Perera. C.G. (2007), Kandy fights the Portuguese. Colombo.

- Perera, F.S.G. (1930), The Temporal and Spiritual Conquest of Ceylon, Colombo: Acting Government Printer.

- Pieris, P.E. (1913), Ceylon the Portuguese Era, Vol. I. 1992nd ed. Colombo: Tisara Prakasakayo.

- Pieris, P.E. (1914), Ceylon the Portuguese Era, Vol. II. 1983rd ed. Colombo: Tisara Prakasakayo.

- Powell, G. (1973), The Kandyan Wars, Great Britain: Trinity Press.

- Ravan-Hart, R. (1964), Ceylon Historical Manuscripts Commission, Bulletin No. 06 ‘The Dutch Wars with Kandy 1764-1766’. Colombo: Government Printers.

- Ravan-Hart, R. (1951), The Great Road, Journal of the Ceylon Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, Vol. IV

- Suraweera, A.V. (2014), The Rajavaliya and the first ever translation of the Alakeshvara Yuddhaya, Colombo: Vijitha Yapa Publications.

- Lankananda, Ven. Labugama (1996), Mandaram Pura Puvatha, Cultural Affairs Department.

- Parangi Hatana

- Balane Hatana

- Rajasinghe Hatana

Well done Chryshane.

Hi Amalka,

Thanks a lot,

Glad you enjoyed it.

I was fascinated by your article. Determined to visit the site and see for myself.

Hi Mr. Silva,

Thank you very much. Yes, its a must see site.

Wow I wish there more people like you undertaking work in Sri Lanka, it was a very interesting read I had no idea of such a fort

Thanks a lot, I will be conducting more studies into this fort. Glad you enjoyed the read.

Great article , Chryshane. Its interesting .